My senior year in high school, I took a junior college-level course about the philosophies of the world. Since it met only three times a week, and I had classes before and after, I would spend Tuesdays and Thursdays in the library. One of those days, I found a novel with Dustin Hoffman on the cover. Having seen The Graduate and Tootsie, I knew who Hoffman was, and I liked what I had seen, so I was intrigued. Also, having been a cross-country runner my first two years, as well as running track-and-field my freshman year, I admit I was intrigued by the title. That title was Marathon Man, by William Goldman, who died Friday at the age of 87. In his book The Season: A Candid Look at Broadway, Goldman describes becoming a fan of Willie Mays after seeing a spectacular catch he made in center field (as well as the throw he made immediately afterward), and “never wavering since”. Though I went on to disagree with Goldman on a lot of things, and disliked some of his work – which I’ll discuss below – I similarly have not wavered in being a fan of his since finding Marathon Man in the high school library that Tuesday or Thursday morning.

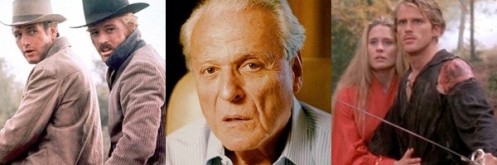

Goldman, of course, was probably best known as a screenwriter, one of the few members of that profession to attain status (barring those, like Preston Sturges, Billy Wilder, and the Coen Brothers, who either went on to direct their own scripts, or always served as writer/director on their films), winning two Oscars for screenwriting (Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, an original, and All the President’s Men, adapted from the book by Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward, though as I wrote in a previous post, how much of it he actually wrote has been disputed). and writing other films (The Princess Bride, based on his own novel) that have become classics. He was also known for what he wrote about Hollywood, particularly his famous saying, “Nobody knows anything”, from his seminal book Adventures in the Screen Trade, to illustrate that no one in Hollywood – not studio executive, director, producer, writer, star, and so on – knew what movies will work and what won’t. But it’s important to remember him as a novelist as well (and I’m not just saying that because that’s how I first knew of his work, though I had dimly remember reading an excerpt of Adventures in the Screen Trade in an old issue of American Film that my father had), not just because he started out that way (he had written five novels before he started his first screenplay, which I’ll also get to below), but also because he always considered himself a novelist first and a screenwriter second, even though his last novel (Brothers, a sequel to Marathon Man) was published in 1986.

Goldman’s first novel, The Temple of Gold (taken from his favorite film of all time, Gunga Din), is a coming-of-age story about Ray, a young man whose friendship with Zachary (nicknamed Zock) becomes a formative part of his life, especially when it turns to tragedy. In the book Which Lie Did I Tell? (a follow-up to Adventures in the Screen Trade), Goldman admitted he started writing out of revenge (he had an alcoholic father and a mother who was deaf (according to Goldman, she lied blamed him for going deaf, and only admitted the truth when she was dying), but though, as i hinted above, the story is not ultimately a happy one, it feels honest and earned. As would be a trademark in his novels, Goldman packed it with autobiographical details (like Ray, Goldman served in the Army, on a base instead of in combat), and while I am wary of the idea that a work being personal on the maker’s part automatically making it good, it certainly helped here. His second novel, Your Turn to Curtsy, My Turn to Bow – Goldman’s favorite book title of his own work – is his one love story, telling a tale of young love. Soldier in the Rain, inspired by Goldman’s time on an army base, is a tragicomic story of a friendship between Eustis and Maxwell, two soldiers on the base, and what happens to them when the base they’re on is going to close and Eustis tries to convince Maxwell, a lifer, they’ll be better off as civilians (it was made into a movie in 1964, directed by Ralph Nelson, with Steve McQueen as Eustis, Jackie Gleason as Maxwell, and co-starring Tuesday Weld, Tony Bill, and Adam West, but Goldman had no involvement; despite the performances, it’s more glib and less deeply felt than the novel). All three of the novels were short, and Goldman, who by that time had moved from his hometown of Chicago to New York City, decided to write a long novel, inspired by the fact many of his friends in New York were trying but failing.

The result, Boys and Girls Together (which is taken from a lyric in the song “The Sidewalks of New York”, by Charles B. Lawlor and James A. Blake – “Boys and girls together, me and Mamie Rorke/Tripped the lights fantastic on the sidewalks of New York”), was a sprawling and involving novel about several characters who come to the city and get involved in making of a play that one of them writes, one directs, and others appear in (as it happens, while writing the novel, Goldman and his brother James – The Lion in Winter – doctored a play, and wrote two other plays – Blood, Sweat & Stanley Poole and A Family Affair – that both flopped on Broadway). While it got mixed-to-bad reviews, Goldman received a huge advance sale, and it became a best-seller in paperback.

This was also the novel that inadvertently led to his movie career. At one point in the writing (it took several years), Goldman became blocked, and had no idea how to continue, only to one day come across a news story that speculated there might be two Boston Stranglers killing people (this was the big real-life crime story of the time), and as he put it, an entire novel dropped in his head. That novel eventually became No Way to Treat a Lady, which Goldman published under a pseudonym (Harry Longbaugh, the real name of the Sundance Kid), and wrote in an unusual format, with a lot of chapters (one as short as one word). Cliff Robertson, best known now for playing Uncle Ben in the 2002 Spiderman movie, but who at the time was a TV and Hollywood actor, read a galley of the novel, liked it (though he thought it was a film treatment rather than a novel, possibly because of its unusual format), and approached Goldman to adapt the Daniel Keyes story “Flowers for Algernon” for him to star in. While Goldman ended up getting fired from that project (which later became the movie Charly, and earned Robertson a Best Actor Oscar), Goldman was called in to work on the dialogue for Masquerade, a spy spoof directed by Basil Dearden (The League of Gentlemen, Victim) and starring Robertson, and became a screenwriter after that.

Though Goldman’s next screenplay, Harper (adapted from the Ross MacDonald novel The Moving Target, the first of his Lew Archer detective novels), starring Paul Newman, was a hit, it wasn’t until Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid that Goldman became a name in Hollywood. Goldman received a huge advance sale for the screenplay ($400,000), the movie, despite bad reviews (Richard Schickel, at the time, called it “The Wild Bunch for people who couldn’t stand The Wild Bunch” – a film Schickel loved – though Schickel would later reverse his opinion on Butch, and Pauline Kael called it “a facetious Western”, and “all posh and josh, without any redeeming energy”), became a big hit, and it was nominated for seven Oscars and won three, including a Best Original Screenplay award for Goldman. Parts of the movie don’t hold up very well – the Oscar-winning score by Burt Bacharach and theme “Raindrops Keep Falling On My Head” (performed by B.J. Thomas) feel awfully glib for a movie that’s supposed to be about people who, despite being “buddies”, don’t know each other as well as they think they do, and are behind the times in ways; in addition, some of the cinematography by Conrad Hall comes off as self-conscious, and Katherine Ross’ role as Etta, the woman shared by Butch (Newman) and Sundance (Robert Redford, in his breakout role), is ill-defined at best and problematic at worst. Still, it’s a good movie about male friendship, and in my opinion, it doesn’t get enough credit for the way it turns certain Western tropes on their head, with Butch, most of the time, getting by on his wits and charm rather than shooting a gun (it feels appropriate that Goldman’s only other Western penned for the screen – Mr. Horn was made for TV – Maverick, was also about a character who survived on his wits and charm, though unlike the TV character played by James Garner, Mel Gibson’s incarnation also knew how to handle a gun).

Despite the Oscar, and despite more screenplay work – more about that below – Goldman continued to occupy himself otherwise. His first non-fiction work, The Season (which he was able to write thanks to the advance sale for Butch), took a look at the 1967-68 Broadway season (probably best known today for James Rado and Gerome Ragni’s Hair, Neil Simon’s Plaza Suite and Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead). While profiling all of the plays that opened on Broadway that year (as well as covering their early out-of-town tryouts in most, if not all, cases), Goldman also took on what he saw as the problems of Broadway at the time – the over-reliance on plays from abroad (particularly Britain) rather than trying to cultivate homegrown talent, the shoddy business practices, and the way Broadway, in general, avoided contemporary concerns, or treated those concerns superficially. Again, parts of this don’t hold up well – his attack on critics (he calls them putrescent in general) is, to say the least, overblown, his chapter on “critics’ darlings (which he described as actresses who let their tics do their acting for them) is pretty sexist, and while his chapter on homosexuals in the theater is well-meaning (he wanted more plays like The Boys in the Band – which had recently opened off-Broadway – where homosexuals could write honestly about their experiences and feelings instead of having to “code” their work) it comes off as problematic. Still, much of it still rings true today, and comes off less as a diatribe than as a fan who wants Broadway to right itself.

Goldman also continued to write novels. The Thing of It Is…, about a songwriter who hates the song that’s become a hit, and who is forced to confront his failing marriage and his Jewish identity (Goldman was inspired to write this after a trip to Europe where he himself confronted his own Jewish identity after visiting a Jewish ghetto in Venice). While No Way to Treat a Lady had been adapted into a film (with Harper director Jack Smight as director, and starring Rod Steiger and George Segal) without his involvement, Goldman was involved in two unsuccessful attempts to film The Thing of it Is…, one with Elliot Gould (after Goldman’s original choice, Redford, backed out) and Dyan Cannon (which ended when director Mark Rydell – who replaced Ulu Grossbard after he backed out – insisted on bringing in another writer and Goldman insisted on getting paid, which torpedoed the project), and the other with director Stanley Donen and producer Robert Evans, which ended when Evans vetoed the male lead choices (James Caan and Alan Alda) and Ali McGraw, who originally wanted the female lead, did The Getaway instead. Goldman did write a sequel to the novel, Father’s Day (about the main character’s relationship with his daughter), and planned to turn the story into a trilogy (with The Settle for Less Club being the proposed title of the third and final entry), but that never happened. Instead, Goldman ended up writing what became his most beloved work, and, along with Butch, his favorite of his own work, The Princess Bride.

As much as I like the movie version of The Princess Bride – it was my fourth favorite film of 1987 – I love the novel even more. Originally inspired by stories he had told his daughters, Jenny and Susanna (one wanted a story about princesses, while the other wanted a story about brides), Goldman, after getting writer’s block, decided to pretend he was “abridging” a long-lost masterwork by S. Morgenstern, which Goldman claimed his father would read to him (Goldman continued the joke years later with another Morgenstern “story”, The Silent Gondoliers), but which, despite having a good story of “true love and high adventure”, as the tagline put it, turned out to be “unreadable” because of chapters dealing with material “irrelevant” to the tale of “true love and high adventure”. Though you could use this as another example of Goldman not writing women particularly well – the title character, well-played in the film by Robin Wright in her film debut, is still a bit of a cipher – it manages the difficult task of sending up adventure stories and love stories while also being a brilliant example of both. And while it ends on a more hopeful note than Goldman’s other work – if still ambiguous (the movie is more sunny) – it still goes into Goldman’s usual dark places, including one character’s difficult relationship with their father, not to mention the torture of the hero.

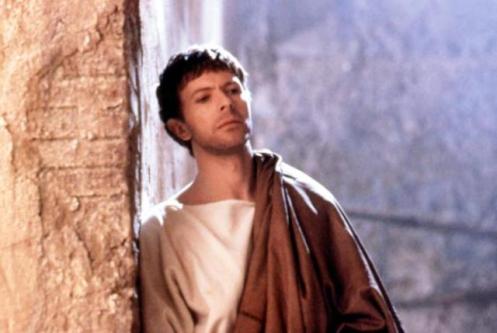

It was around this time Goldman’s editor since Soldier in the Rain, Hiram Haydn, died (in an introduction to a later edition of Marathon Man, Goldman calls him a father figure), that Goldman’s novels became more genre and more commercial. Marathon Man, which is about a grad student in history who becomes the target of an ex-Nazi, was a thriller. Magic, with a plot similar to a segment of the anthology film Dead of Night (a ventriloquist is suffering from a split personality and is also a murderer), is a horror novel, Tinsel, about a producer planning to make a film about Marilyn Monroe’s final days, and the three women desperate to play the part, was of course a Hollywood novel. Control, which brought together a disparate group of characters and a plot to kill Alexander Graham Bell, was science fiction. Heat (not to be confused with the Michael Mann film) was a combination of a crime novel and an action story, and Brothers was a sequel to Marathon Man. Only The Color of Light was of a piece with his earlier, literary work, about a writer struggling with his life and his writing. Still, even though he may have gone in a different direction in his writing, Goldman still, at his best, writing characters that you could get emotionally involved in, as well as stories that you could get involved in as well. For example, Marathon Man – which, along with The Princess Bride and The Color of Light, is my favorite of his novels – has both Babe, that grad student in history, and Doc, his brother (unbeknownst to Babe, Doc is a lot more than he seems) both affected by the suicide of their father, a former professor who lost his job during the McCarthy era, and killed himself because of that. It was also a novel where Goldman inserted a lot of his tastes in what he liked of movies (Babe takes his girlfriend to a double bill of movies directed by Ingmar Bergman, Goldman’s favorite filmmaker), sports (Scylla, an assassin, manages to overcome someone trying to kill him by using a move he saw Earl Monroe pull on Walt Frazier once on the basketball court) and wine (Doc bores Babe in talking about wine, but also uses his knowledge to soften up Babe’s girlfriend Elsa before he interrogates her about her real motives), among other things.

Brothers turned out to be Goldman’s last novel (though he had planned a sequel to The Princess Bride, called Buttercup’s Baby, it never panned out). By that time, he had written Adventures in the Screen Trade, which, 35 years later, still remains the best book ever written about Hollywood. Of course, it is known today for his famous line “Nobody knows anything”, which demonstrated that while people in Hollywood knew what worked in the past, they did not, could not, and would not, know what would work in the future (as an example, Raiders of the Lost Ark, the first team-up of George Lucas and Steven Spielberg, was turned down by every studio except for Paramount). But it’s a lot more than that. Though I don’t share Goldman’s contempt for directors (he wrote they are not artists and get too much credit for the films they do) or stars (he wrote they were too often concerned with how to make the material work for them, rather than how to make the material work), he, along with Pauline Kael, were my major influences in being skeptical of the auteur theory (ironic, since Goldman was not a fan of Kael’s, and vice versa), and giving me awareness of how movies were often based on accommodating the stars, and not to the benefit of the movie. As I am pre-disposed to not see studio executives in a good light, I think Goldman is often too easy on them, perhaps due to his close relationship to some of them, but he does point out how the executives’ reluctance to believe the story is the real star of a film has led to some questionable decisions, to say the least. I also think there are good movies that are more character-driven than story-driven – and often prefer the former – but Goldman’s insistence that “screenplays are structure” (which he meant as his other big theme of the book, along with “nobody knows anything”) is a useful guide. Goldman was also honest about his own failings, included perspectives from other people involved in making a film (in a section where he asks such people as cinematographer Gordon Willis, editor Dede Allen, and composer David Gruisin about hypothetically adapting one of Goldman’s short stories, “Da Vinci”, to the screen), and gave insight about the craft and the process of making a film.

More importantly, Goldman’s book taught me to respect screenwriters and screenwriting, and to shy away from the easy assumption often made by most critics that if a film doesn’t work, it’s always the screenwriter’s fault (even though it is pointing out the script is the most important part of the film). Though he disparaged any idea of screenwriting being an art, and insisted it was just a craft (albeit an important one), Goldman’s book was an important influence for me in viewing screenwriting as an art (along with Richard Corliss’ book Talking Pictures). So it’s sort of sadly ironic that while I revere Goldman as a fiction writer as well as a non-fiction writer – in addition to The Season and Adventures, he also co-wrote (with sportswriter/novelist Mike Lupica) a great book about a year in the life of New York sports teams (Wait Till Next Year), and he wrote an entertaining book about the year he was a judge at both the Cannes Film Festival and the Miss America contest (Hype & Glory), and I liked his follow-up to Adventures (Which Lie Did I Tell?) even if I disagreed with some of it (I don’t share his contempt for Saving Private Ryan, for example) – I am not necessarily a fan of many of the movies where he’s listed as screenwriter.

Of the films in which he’s credited on, only All the President’s Men and The Princess Bride are films I like without reservations. I’ve mentioned my slight reservations about Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid; I also like, with reservations, Harper, The Hot Rock, The Great Waldo Pepper, Marathon Man, Maverick, and Absolute Power. The Stepford Wives didn’t work for me (though given the fact I have not been a fan of Bryan Forbes’ previous work, that’s where the fault may lie, especially with Goldman’s assertions that Forbes re-wrote much of the film), nor did A Bridge Too Far (I don’t agree with Francois Truffaut’s assertion that there’s no such thing as a truly anti-war film, but if I did, this film would be the first one I’d present as evidence), Magic (though, admittedly, it’s a tough novel to adapt), Misery (the novel scared the shit out of me, and unfortunately, the movie didn’t), Year of the Comet (I don’t dislike this as much as critics and audiences at the time, did, but it’s too arch to be the light entertainment it wants to be), The Chamber (though, admittedly, the source material wasn’t great either), The Ghost and the Darkness (as with Year of the Comet, I didn’t hate this, but while the lion sequences are scary, the humans aren’t as interesting), The General’s Daughter (a thoroughly detestable movie, though since Goldman’s not the only credited writer, and Simon West is a hack director, it’s hard to know who to blame), and two more Stephen King adaptations, Hearts in Atlantis and Dreamcatcher (admittedly, not a fan of either source).* As with his novels, Goldman has a good ear for dialogue, and he puts his personal obsessions into the movies in interesting ways (even in Hearts of Atlantis, one of his less successful movies, there’s a nice scene where the main character, played by Anthony Hopkins, reminisces about seeing Bronko Nagurski during the game he came out of retirement, which Goldman actually saw), but the emotions and characters he brings to life in his novels do not come to life in the movies he’s written or co-written.

Still, this should not diminish Goldman’s accomplishments. In an age when writers and creativity continue to be devalued, he has consistently advocated the idea writers and their work should be treated with respect, not the contempt they so often are. While he was often disparaging about his own work as a writer, he wrote two of my favorite movies of all time, three of my favorite novels of all time, and the arguably the most important book about Hollywood ever written. That’s a good enough legacy for anyone.

*-Memoirs of an Invisible Man and Chaplin I didn’t include, even though he’s credited on both, because on the former, while he was the original writer, he was re-written after he quit and a new director came on board, while on the latter, he was one of many writers as well.

In his book Making Movies, Sidney Lumet wrote about how, when he decided to direct a film (he rarely wrote it, so he was almost always directing someone else’s work), he always asked himself, “What is this movie about?” Not the story, but the theme of the movie, or what grabbed him about it, whether the theme was underlying or right up front. One theme Lumet tackled a couple of times, in films as varied as Daniel, Running on Empty, and Family Business, was, as he put it, “Who pays for the passions and commitments of the parents?” This theme ended up being a major underlying theme of The Americans, which ended its six season run this past Wednesday.

Of course, it wasn’t the only theme of the series. Show creator Joe Weisberg (an ex-CIA agent and novelist) and co-executive producer Joel Fields (a veteran TV producer) were revisiting the Cold War, and avoiding the glow of nostalgia to portray a time more complicated than many remember it to be. The series was also a portrait of a marriage, with Elizabeth (Keri Russell) and Philip Jennings (Matthew Rhys) having to be partners not only at home, as well as their “respectable” business (they owned a travel agency), but also their real work, as Soviet spies undercover near Washington D.C. And just as the show avoided easy answers in looking at the Cold War and the Jennings’ marriage, it also tackled the 80’s in a way that avoided the kitsch of most stories looking back at that decade. However, as with other shows with anti-heroes (from our point of view, anyway) at their center, The Americans also showed the toll spying took on the Jennings’ children, Paige (Holly Taylor) and Henry (Keidrich Sellati).

When the series first began, Paige and Henry seemed like your normal kids from a stereotypical nuclear family. Paige was interested in her studies, while Henry was interested in sports and games. Both, as they grew older, became interested in the opposite sex; Paige with Matthew (Danny Flaherty), the son of Stan Beeman (Noah Emmerich), the FBI agent who was the Jennings’ neighbor, while Henry never had anything steady, though he did become infatuated with one of his teachers, as well as Stan’s then-wife Sandra (Susan Misner). But as the series progressed, you could see Paige and Henry react to their parents’ unconventional lives (no relatives, no friends outside of Stan, being out at all times, and often until late hours). For Henry, this manifested itself in the way we’re used to seeing kids who have been neglected by their parents on-screen – playing on his computer or with video games, fooling around with himself, and finding another parent figure (in this case, Stan). Paige’s situation, however, was much more complicated.

At the end of Season 1, after Elizabeth and Philip escaped capture (though not without Elizabeth getting shot), Paige took a look inside the laundry room where her parents often conducted business or had private conversations, and while she didn’t find anything incriminating (Elizabeth and Philip were too good at their jobs for that), her curiosity, and suspicion, were piqued. At first, except for a furtive visit early in Season 2 for the “Aunt Helen” Elizabeth had supposedly been recuperating with, her reaction didn’t come out in obvious ways. Most teenagers engage in some form of rebellion, but Paige’s method of rebellion was unusual; she got religion. She joined a church, became friends with Pastor Tim (Kelly AuCoin), the head of the church, and became an active participant. Elizabeth and Philip, being the product of a country that saw religion as the opiate of the masses, were less than thrilled, even though, ironically, Paige was, through the church, participating in things Elizabeth professed to believe in, such as protests in favor of nuclear disarmament. At first, all of the arguments involving Paige centered on her religious beliefs. However, in the season 2 finale, “Echo”, Claudia (Margo Martindale), one of Elizabeth and Philip’s handlers, revealed to them the Centre wanted Paige, and eventually Henry, to join the family business and become spies. For the majority of Season 3, Elizabeth and Philip quarreled over this plan – Elizabeth was for it, somewhat, while Philip was adamantly against it – until Paige forced their hand.

In the episode “Stingers” – my vote for the best episode of the series – after Elizabeth and Philip returned from one of their missions one night, Paige confronted them in the kitchen, and demanded to know what they were really up to. Ironically, it was Philip who indicated he and Elizabeth should answer this question, and while they didn’t tell her everything, they did admit to Paige they worked for the Soviet Union (Elizabeth had been laying the groundwork by talking about the things she believed in, that she thought Paige would appreciate). Paige’s first reaction, was shock, and even a little outrage. And while many fans were upset about her subsequent action, I was not; she called Pastor Tim and told him all she knew. This, of course, put Elizabeth and Philip’s lives at risk – both of them were outraged when they found out, and Paige was apologetic – but while Pastor Tim and his wife were understandably nervous around Elizabeth and Philip (especially after Pastor Tim goes missing in the Season 4 episode “Munchkins” during a trip to Africa, though he was eventually found), and he encouraged Paige to come forward with what she knew at first, eventually, he decided not to betray the Jennings family (though in his diary, he does describe Elizabeth and Philip as monstrous, and eventually takes a job in Buenos Aires to get away from the situation at the end of Season 5).

More interestingly, Paige found herself eventually becoming a spy, or at least acting like one. At first, she was just, reluctantly, keeping tabs on Pastor Tim and his wife (after Elizabeth ordered her to in no uncertain terms), and being secretive from others (which is why she eventually broke things off with Matthew, because she couldn’t stand keeping the truth from him). But gradually, Paige became drawn into her parents’ world, partially to learn to take care of herself (after she witnessed Elizabeth dispense of a mugger in the episode “Dinner for Seven”), though mostly because she was becoming somewhat intrigued by her parents’ world, and perhaps had deluded herself into believing what Elizabeth was telling her, that they were ultimately doing “good” work, even though she kept expressing doubts. And in Season 6, Paige was actually working directly for Elizabeth with spying (at the end of Season 5, Elizabeth told Philip he should quit spying, and he agreed). It was only simple stuff – following someone by car or on foot, staking out a location, and even adorning simple disguises (not as elaborate as the wigs Elizabeth and Philip wore) – but Paige did get into the work, as well as meeting with Claudia and Elizabeth to talk about life in the Soviet Union, and even offering to get close to a Senate intern (which Elizabeth vetoed, though Paige ended up sleeping with him anyway). Paige is even able to defend herself against two boys who try to attack her in a bar (in “The Great Patriotic War”). Elizabeth, though, had admitted to Philip Paige might not be cut out for spying, and told Paige (in “Harvest”) to apply to work for the State Department as an intern.

However, in “Jennings, Elizabeth”, the next-to-last episode of the series, Paige accuses Elizabeth of seducing another Senate intern, and when Elizabeth unconvincingly denies it, Paige calls her mother a whore. Elizabeth tells her off in turn, saying how privileged she is compared to what Elizabeth grew up with. Unfortunately, events soon force their hand. Philip, who has reluctantly come back to the fold, is meeting up with a priest whose superior has just betrayed the priest to the FBI (as Stan has suddenly become suspicious of the Jennings family), and Philip is barely able to escape and make a coded call to Elizabeth to basically tell them they need to flee. Philip and Elizabeth meet at a safe house after Elizabeth has packed what they need, and that’s when the series takes an unexpected turn. Henry has at boarding school, pursuing both his interest in math and hockey (early in the season, we see Philip cheering him on at a game), though Philip had worried he wasn’t going to be able to keep paying for it, especially after his travel agency business starts to go south. But it seems like Henry has made a life for himself outside of the family (made clear in the episode “Rififi”, when Henry comes home for Thanksgiving, only for Elizabeth and then Philip having to go on a mission), and Philip tells a shocked Elizabeth in the series finale (“START”) they have to let him go.

Elizabeth and Philip do end up taking Paige – reluctantly on Paige’s part, as she’s still angry at her mother, until she finds out what’s going on – and after the three of them manage to talk their way out of a confrontation with Stan (who has been staking out Paige’s apartment building), they make their escape. After making one stop to call Henry on a pay phone to say goodbye without actually saying goodbye (Paige is too overcome with emotion to say anything), they take a train to Canada so they can fly back to the Soviet Union, which is when we get our final shock. At the border, without telling anyone, Paige gets off the train, leaving both Elizabeth and Philip in shock, though they continue to the Soviet Union. In short, everyone gets separated in an uncertain future – Elizabeth and Philip in Moscow, Henry still at school (though knowing now the truth, after Stan visits and tells him), and Paige on her own (she goes back to Claudia’s safe house, which is now empty, and downs a shot of vodka).

Some have complained the show essentially let the Jennings family off the hook by letting them escape. But consider their family has broken up – as much as Elizabeth put her country above everything, she still cared for her children, and Philip as well – and both Paige and Henry face uncertain futures (they both have school, but there’s a question of who’s going to pay for it, not to mention the suspicion they’ll be under). And that’s not even mentioning the fact we know what the characters don’t – the Cold War (at least in that form) will end in a couple of years (the last season of the show took place in 1987), and Elizabeth and Philip’s “cause” will be very different (and will they get to back and visit Paige and Henry? Who knows?). The Americans was a show about espionage. It was a show about people who believed they were doing the right thing, and doing horrible things to continue to do that right thing. It was a show about a partnership. But it was also show about a family. All of which (except for the espionage part) is the template of the show that was considered the game-changing show of the last 20 years or so, The Sopranos, and The Americans was the series that, in my opinion, did the best of following the template of a show about a family whose patriarch (or matriarch, or both) did horrible things in the name of what they thought was the right thing. But even more than The Sopranos, The Americans showed how the children paid for the commitments of the parents.

Gene Hackman and Lee Marvin in Prime Cut (1972).

As much as I’m a fan of the major acclaimed American movies of the late 1960’s and early 1970’s – as well as the foreign language movies that came out during that time – I can understand why some people may roll their eyes at yet another tribute to them. It’s not just the fact this was almost exclusively a province of Great White Males, with not much room for women or minorities (mistreated both in front of and behind the camera). Its also the fact people who sing the praises of these movies can sound as obnoxious about them as baby boomers who claim theirs was the “greatest generation” (as well as theirs being the only one that really protested anything), or as fatuous as the film professor in Andrew Bergman’s great comedy The Freshman (he’s brilliantly played in the movie by Paul Benedict) when he’s lecturing students about The Godfather Part II (which happens to be my favorite movie of all time). Finally, while movies like the first two Godfather films, Nashville and Taxi Driver may have been the ones that had critics then and now wax rhapsodic about the movies, as well as the people who made them (Coppola, Altman, Scorsese, and others) and the actors who appeared in them (Pacino, Nicholson, De Niro and others), with some exceptions (the first Godfather), these weren’t the big hits of the 70’s. Instead, they were blockbusters like Love Story, The Poseidon Adventure, The Exorcist, and The Towering Inferno.

Barry Newman in his GTO in Vanishing Point (1971).

But what about the “B” movies, or genre movies, of the time? There have been books written about some of the specific genres of the time – horror movies, blaxploitation movies, westerns, and so on – but what Charles Taylor’s Opening Wednesday at a Theater or Drive-In Near You: The Shadow Cinema of the American 70’s aims to do is give an overview of those types of movies, ones that are among his favorites and ones that, for the most part, aren’t as well remembered (and, in some cases, aren’t even available on DVD, Blu-Ray, or streaming). Taylor was a fan of those acclaimed 70’s movies, so he’s not out to debunk those (though he is out to debunk another type of movie; see below), but to illustrate the pleasures these lesser-known films offer.

Kris Kristofferson and Gene Hackman in Cisco Pike (1972).

Opening Wednesday covers a broad range of genres, including crime movies (Aloha, Bobby and Rose, Born to Win, Prime Cut), car movies (Citizens Band, Two-Lane Blacktop, Vanishing Point), blaxploitation movies (while the chapter on these is devoted to Coffy and Foxy Brown, Taylor also writes about the genre in general), period dramas (American Hot Wax – which has as much comedy as drama – and Hard Times), westerns (Ulzana’s Raid), horror/thriller (The Eyes of Laura Mars), conspiracy thrillers (Winter Kills), cop movies (Hickey and Boggs), and revenge dramas (Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia). Blaxploitation movies were exclusive to the 70’s (almost all the attempts to revive the genre have been satiric, such as Black Dynamite and I’m Gonna Git You, Sucka!), as were conspiracy thrillers for the most part (though there have been occasional attempts to revive it), and car movies, and westerns were starting to wane (until being revived in the 90’s with the one-two punch of Dances with Wolves and Unforgiven; they’ve gone hot and cold since then, on TV (Deadwood) and in movies (The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford)). The other genres are still around, though only horror/thriller movies seems to be made as much as they were in the 70’s.

Pam Grier in Foxy Brown (1974).

Taylor is also spotlighting lesser-known directors of the time with this book. Robert Aldrich (Ulzana’s Raid) was beloved by auteur critics at the time, but while he had a couple of successes in the 70’s (The Longest Yard), his career was winding down. Likewise, while Sam Peckinpah (Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia), who was equally loved and reviled in critical services, had success in the late 60’s/early 70’s (The Wild Bunch, Straw Dogs), alcoholism and too many battles with studio executives had taken their toll. Monte Hellman (Two-Lane Blacktop) has continued to make movies, but he has remained a cult figure, just as he started out in the 60’s. Though Jack Hill (Coffy and Foxy Brown) has become a cult figure thanks to a revived interest in blaxploitation films (as well as big-name fans like Quentin Tarantino), he made only a couple of more films after those. Both Bill Norton (Cisco Pike) and Floyd Mutrux (Aloha, Bobby and Rose, American Hot Wax) moved into television. William Richert (Winter Kills) ultimately has acted in more films than he’s directed, and while he worked somewhat steadily as a director in the 70’s and 80’s (though to decreasing returns), Richard C. Sarafian (Vanishing Point) became known more for his acting as well. Hickey & Boggs remains the only film actor Robert Culp ever directed. Only Jonathan Demme (Citizens Band), Walter Hill (Hard Times), Irvin Kershner (Eyes of Laura Mars) and Michael Richie (Prime Cut) enjoyed any major success in the 80’s and/or beyond. Though Demme did struggle in the 80’s, he directed cult hits such as Stop Making Sense and Something Wild, and made the Oscar-winning film The Silence of the Lambs, Hill has worked steadily and made such hits as The Warriors and 48 Hours, though Kershner, who started out in the 60’s, only made a few films in the 80’s, one was Sean Connery’s last James Bond film (Never Say Never Again, and one was a little film called The Empire Strikes Back, and Richie made The Bad News Bears and Fletch, among other films.

Pam Grier in Coffy (1973)

A devotee of Pauline Kael (he thanks her in the acknowledgments at the end, calling her the reason he wanted to become a critic), Taylor does analyze the films he reviews, but like Kael, he primarily wants to communicate the visceral part of the movie, to make you understand how it *feels*. This, for example, is from the opening paragraph of his essay on Two-Lane Blacktop:

“…we’re in a small-town service station North Carolina service station at what appears to be about six A.M. on a rainy Sunday morning. Maybe it’s Saturday. The characters themselves aren’t sure. These hot-rodders have pulled into the station to attend to a busted carburetor and it’s just as well the place is closed. The mood of this drizzling dawn seeps into everything. Pretty soon they’ve drifted away from the task at hand to nip at a bottle, doze, wander the town. One or two people are visible on the street but something in the still, quiet air makes it feel like nothing’s about to change. Saturday mornings in town give the promise of the bustle to come. Sunday never shakes off its sleepiness.”

Warren Oates and Laurie Bird in Two-Lane Blacktop (1971).

As you might be able to guess from that excerpt, Taylor is also trying to stress the fact these movies are also showing a corner of the U.S. that doesn’t often get shown; not just the North Carolina as described above, but the Kansas City of Prime Cut, the Depression-era New Orleans of Hard Times, and the small Southern town of Citizens Band (though he does look at movies that take place in familiar cities, like the New York City of Eyes of Laura Mars, and movies that travel to multiple places, like Winter Kills). He also explores how many of these films communicate with film history, or their context in it, particularly in the works of three filmmakers he singles out: Preston Sturges (whom Taylor calls “the greatest American comic filmmaker of the sound era”), Howard Hawks (the “great modernist” whose films were about “communities of…drifters who coalesce around some task or purpose”), and John Ford (whose classic Stagecoach is about “the essential tension of American life, the desire to belong and the desire to light out for the territories”).

Burt Lancaster in Ulzana’s Raid (1972).

Taylor sees, for example, the comic sensibility of Sturges in Citizens Band – particularly in the subplot of a trucker (Charles Napier, a Demme regular) who happens to be married to two different women (Marcia Rodd and Ann Wedgeworth), and who both come into town (unaware of the other) to check up on him after he gets into an accident. But there’s also a Hawks-like spirit to the movie as well, particularly when the hero, Spider (Paul Le Mat, who also plays the lead in Aloha, Bobby and Rose) organizes other CB enthusiasts to help look for his missing father (Roberts Blossom). And you can see Ford in Hard Times (Hill, a classicist director, is a devotee of Ford and Hawks) in how people on the dregs, like the hero (Charles Bronson), an aging boxer, and his loudmouthed manager (James Coburn), look out for each other (even if Coburn inadvertently gets over his head). And while Sturges may not have gone as far as Winter Kills (based on the novel by Richard Condon) – in which the conspiracy theories of John F. Kennedy’s assassination get dropped through the proverbial rabbit hole to create a warped black comedy – he certainly would have recognized its comic spirit. Taylor also shows how some filmmakers have quoted from those movies, Quentin Tarantino in particular (Jackie Brown is one long love letter to the Pam Grier of Coffy and Foxy Brown, and the second half of Death Proof references Vanishing Point).

A doo-wop group rehearsing in American Hot Wax (1978).

Taylor’s primary purpose for the book, however, is to demonstrate how these movies, according to him, differ from the genre movies made today. Not only does he argue their stories are told more coherently than today’s blockbusters – even stories as outlandish as Eyes of Laura Mars (a serial killer movie where fashion photographer Faye Dunaway somehow sees through the eyes of the killer when he’s committing his murders), Winter Kills (see above) or Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (a revenge tale the way only Peckinpah could have made it) – but more importantly, that they stay connected to the world we live in more than the blockbusters and genre movies of today. The first example comes in the introduction with a movie that isn’t covered in the book, but was one of the inspirations for it; Jonathan Kaplan’s White Line Fever, about a Vietnam vet (Jan-Michael Vincent) who battles corruption in the trucking industry. I’ve not seen the film (though, like Taylor, I’ve enjoyed some of Kaplan’s other movies, like Over the Edge – still one of the best teen movies ever made – and The Accused), but apparently, it has things like Vincent and his wife (Kay Lenz) eating spaghetti for days on end because they can’t afford anything else, or Lenz wearing the only expensive dress she owns to court when she wants to help Vincent out of trouble, or Lenz confessing to her brother she might have to get an abortion. Taylor brings up other movies in the book with details like that, such as a waitress telling Charles Bronson in Hard Times that he only gets one refill for a nickel cup of coffee, or the sadness in Roscoe Lee Browne’s eyes in Cisco Pike when he refuses to buy Kris Kristofferson’s guitar (Browne owns a music shop), even though he knows Kristofferson’s claims he’s going back into the music business aren’t going to amount to anything, or how, in American Hot Wax, Alan Freed’s (Tim McIntire) days when he’s not being a DJ are basically meetings, meetings and more meetings.

Faye Dunaway in The Eyes of Laura Mars (1978).

In trying to make his case, Taylor does fall into the trap that has befallen a certain strain of critics, who lay the blame of the blockbuster era on Star Wars. I have never been the fan of George Lucas’ saga that friends and family have, and I certainly agree with the criticism that Lucas seems to feel any indication, or mention, of sex would complicate his characters, and his stories, too much for him and for much of its audience. That said, blaming everything on Star Wars (as well as on Spielberg, another frequent target of the “Yesterday Was Better” club) is, I feel, pretty short-sighted. First of all, not to put a fine point on it, but Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho did what Lucas and Spielberg have long been accused of – dressing up a B-movie plot with A-movie actors and storytelling – and has inspired more rip-offs than Lucas and Spielberg have, yet you don’t get a million think-pieces saying how Hitchcock and Psycho ruined movies. Secondly, as I pointed out before, this ignores the fact blockbusters were still making much more money than the critical faves of the 70’s, and Lucas’ (and Spielberg’s) films were better than most of those films (I’d rather watch Star Wars again than sit through one minute of The Towering Inferno, or The Exorcist, again).

John Huston (foreground) and Jeff Bridges in Winter Kills (1979).

That’s not the only flaw of the book. Like Kael at the time, Taylor sometimes seems to think outrage, anger, and cynicism automatically equals self-loathing (even, at the same time, he champions the films in the book, as well as the critical favorites of the decade, for not providing happy endings or easy answers). In an offhand dismissal of Chinatown (which I, and many others, consider one of the best movies of the decade), which he thinks is full of “cheap and easy despair”, Taylor writes, “Seeing (Chinatown), you could forget that America had just toppled a corrupt presidency”, without mentioning (a) that corrupt president was pardoned and did no time for his crimes, and (b) as Chinatown predicted, power mongers continue to get away with their rape of the land and the people.* And while there’s a lot of nuanced discussion, for example, of blaxploitation movies – Taylor acknowledges their paint-by-numbers plots and dialogue, their sexism, and their crude and cheap cynical nature, yet also does get at the reasons why they resonated with African-American audiences at the time (as well as being in line with the B-movies white audiences embraced at the time – yet when it comes down to defending Peckinpah from charges of sexism, while he acknowledge the misogyny in movies like The Getaway and Straw Dogs, only seems to deliver a half-hearted defense (pointing out the comeuppance a misogynist receives in Cross of Iron, as well as the way the hero in Ride the High Country gets himself killed to protect women from being raped) before dismissing any critic of Peckinpah’s ugly side as people “turning an artist’s output into a balance sheet of correct and incorrect attitudes” (I agree somewhat with this sentiment, but it’s done in a rather dismissive manner).` Finally, he takes what I think are some cheap shots at, among others, Joni Mitchell (when discussing Cisco Pike).

Warren Oates in Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974).

Still, for all of its problems, the book is finally worth tackling. Except for Two-Lane Blacktop, a film I admire more than I like (except for Warren Oates’ performance, which I flat-out love), all of the movies under discussion are well worth watching (two of them – Citizens Band and Winter Kills – made my top 10 lists for the year of their respective U.S. release dates, while two more – Vanishing Point and American Hot Wax – made my honorable mention lists for the year of their respective U.S. release dates), and Taylor does a good job of distilling what works about them (his description of Vanishing Point – “hot rod movie as tone poem” – cuts to the quick), even while acknowledging some of their flaws. Like my other favorite critical study of 70’s films – British critic Ryan Gilbey’s It Don’t Worry Me, about who Gilbey thought were the 10 major American directors of the 70’s (including Demme) – Taylor honors the complexity of the films by not putting them into a nostalgia box (even if he does belong to the “Yesterday was better” club when it comes to these movies), and at his best, writes about them with clarity and obvious passion. That makes Opening Wednesday at a Theater or a Drive-In Near You, for all of its faults, something to savor rather than to roll your eyes over.

*-Taylor, like Kael before him, also dismisses Arthur Penn’s Little Big Man (from the Thomas Berger novel), a revisionist western, in the same way. I confess I haven’t seen it in a long time, so I can’t make any judgments on that, though I do like other Penn films such as Bonnie & Clyde, Alice’s Restaurant (both of which Taylor praised), and Night Moves.

Bill Cosby and Robert Culp in Hickey & Boggs (1972).

`-Taylor’s essay on Hickey & Boggs was written before the rape allegations against Bill Cosby started coming to light. I can’t imagine what Taylor, who spends a lot of time in the essay talking about the appeal of Cosby in general and on I Spy and in the movie in particular, would make of that.

The Beatles performing on The Ed Sullivan Show

About 2/3 of the way through Robert Draper’s fine book Rolling Stone Magazine: The Uncensored History, he writes about a meeting between Jann Wenner and Charles M. “Chuck” Young at the magazine’s New York City office following the memorial for John Lennon. Wenner, of course, was the co-founder, magazine editor and publisher of the magazine (he’s still the publisher), and while he had been a rebel in his teen years and turned to rock music as an outlet for that rebellion, he was now embracing, and publicizing, rock music as celebrity. Young, another teen rebel in many ways, embraced a type of rebellious music (the punk music of the 70’s, in New York but especially in Britain) that offended Wenner, and sought to distance the music from celebrity worship, which he thought cheapened it (one of the few tastes the two of them shared was a love of the Rolling Stones, but even here, Wenner was more a Mick Jagger guy, while Young was more Keith Richards). At the meeting, Wenner, who was still teary-eyed, gushed to Young about the music played at the ceremony. Young, not a Beatles fan in general, said he hated it because, “They played his most insipid shit, and they didn’t play a single rock-n-roll song.” Wenner, who was left speechless at first, replied that he thought it would have been inappropriate.

Draper was obviously using this as a way to illustrate the difference between the two on this and rock music in general, and was clearly on Young’s side. When I first read the book (not long after it came out), I have to admit, though, I was on Wenner’s side; at a memorial service for a giant such as Lennon, what was wrong with being sentimental? Now, however, I’ve come back to Young’s and Draper’s point of view, though for different reasons. As with all other pop culture from the 1960’s (as well as before and after), the Beatles, and Lennon, have been placed in a nostalgia box, with all of the rough edges sanded off, so people can feel comfortable with them. There’s something more particular about the way it’s been done with the Beatles, however, as if those who are guarding the legacy of Lennon and his former group are trying to purge any hint of Charles Manson or Albert Goldman from memory, lest it taint the group. While this is understandable, it’s also resulted in some bland tributes over the years (case in point; the Grammy’s 50 year tribute to them, enlivened only by Dave Grohl’s rousing version of the rarely-played Beatles’ song “Hey Bulldog”). So I was skeptical in checking out In Their Lives: Great Writers on Great Beatles Songs, edited by Andrew Blauner (with a note from Paul McCartney), as it might have been just another example of this. Fortunately, the book is much more idiosyncratic, and enjoyable, than that.

Blauner, who has edited other anthologies (on baseball, Central Park, and Boston, among other topics), was able to get 28 writers (and one add-on; author Francine Prose, of Household Saints and other works, also included a contribution from her granddaughter Emilia Ruiz-Michels), and from a wide variety of backgrounds. Rosanne Cash and Shaun Colvin are singer-songwriters, Bill Flanagan, David Hadju, Alan Light, and Jon Pareles are music critics (for Flanagan, Hadju and Light, among other things), David Duchovny is an actor, Prose, Peter Blauner, Amy Bloom, Pico Iyer, Rick Moody, Joseph O’Neill, Elisa Schappell, Mona Simpson, and Jane Smiley are novelists, Roz Chast is a cartoonist, Chuck Klosterman and Touré are cultural commentators, Gerald Early is a college professor, Thomas Beller, Nicholas Davidoff, and Alec Wilkinson are non-fiction writers, Rebecca Mead writes and oversees the “Talk of the Town” section for The New Yorker (several contributors, including Wilkinson, either are contributors to the magazine or have written for it in the past), Maria Popova is a blogger about books, Ben Zimmer writes about language for The Wall Street Journal and other publications, Adam Gopnik is a book critic for The New Yorker, and John Hockenberry is a journalist for NPR. So they each bring their own experiences to the Beatles songs they write about.

Playing their last concert at Shea Stadium

Many of the people writing in the book were children when the Beatles first came to America, so we get a lot of personal reminiscence. Chast writes about how “She Loves You” felt like an introduction to a world she didn’t even know existed (she was almost nine years old when it came out), Bloom (who writes about “Norwegian Wood”) and Smiley (who tackles “I Wanna Hold Your Hand”) both talk about seeing the band on The Ed Sullivan Show the first time, Mead writes movingly of how she links “Eleanor Rigby” with her childhood friend Chrissie and her family (likewise, Beller partly associates “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” with a friend named Brian and his family, though whom he first heard the band). Popova mentions “Yellow Submarine” was a song her parents used to sing to summon her, Early remembers “I’m a Loser” as a song he latched on to even though the African-Americans he grew up with largely dismissed it (as well as the band in general), and Zimmer links his love of “I Am the Walrus” with his childhood love of “inspired nonsense” such as Lewis Carroll (whose works inspired the song).

Their animated characters in Yellow Submarine.

But you also get people diving into the history of the songs they write, or looking at the structure of the lyrics and music. Of course, from the critics, this is expected, and you get some ace work here. Pareles, the music critic for The New York Times, talks about the way “Tomorrow Never Knows” was put together, from Lennon’s lyrics being inspired by Timothy Leary and Gandhi, to the Indian instruments George Harrison contributed, to the magnetic tape sound Paul McCartney came up with, to Ringo Starr’s drum work. Light mentions how McCartney’s bass line in “I Saw Her Standing There” is derived from Chuck Berry’s song “I’m Talking About You”. And Hadju writes how “You Know My Name (Look Up My Number)” was inspired by Lennon and McCartney’s shared love of “The Goon Show”, as well as them making fun of the entertainers of their parents’ generation. But they’re not the only ones who break down the songs like this. Mead, in her chapter on “Eleanor Rigby”, also discusses the real people the song was based on, as well as mentioning the different parts each band member came up with (Starr was the one who came up with Father McKenzie “darning his socks in the night when there’s nobody there”). Simpson discusses the article that apparently inspired “She’s Leaving Home”, as well as the fact Lennon’s chorus in the song (“We struggled hard all our lives to get by”) was inspired by things his Aunt Mimi (his guardian growing up) said to him. And though Iyer says he isn’t a particularly big fan of the band (Van Morrison, Leonard Cohen and Joni Mitchell – three artists I personally revere as well – he says are more his speed), he’s able to dissect how the simplicity of the lyrics and music make it work for him.

On the Magical Mystery Tour.

“Yesterday”, of course, is one of the Beatles’ songs that’s always talked about, and the book does hit some of the more obvious songs, like “She Loves You”, “I Wanna Hold Your Hand”, “Eleanor Rigby” (which is my personal favorite of their songs), and “A Day in the Life”, among others. But the book also includes songs that aren’t as well-remembered. In addition to “You Know My Name (Look Up My Number)” (which Hadju admits is usually listed among the worst songs they ever wrote and recorded by the band), there’s also Touré writing about “The Ballad of John and Yoko” (inspired partly by Lennon’s newfound love of Yoko Ono, but also of his weariness with life in the band after the backlash caused by his notorious “we’re more popular than Jesus” remark), Blauner tackling “And Your Bird Can Sing” (one of the best and most overlooked songs from Revolver), Wilkinson discussing “She Said She Said” (another one of the underrated songs on Revolver, and inspired by something Peter Fonda said to Harrison after a bad LSD trip), and Duchovny writing about “Dear Prudence” (from my personal favorite Beatles’ album, The White Album; it was inspired by Mia Farrow’s sister “Prudence”, who had gone to India the same time as they did, to meet the Maharishi). And while there’s no mention of Albert Goldman, Klosterman goes head-on with the issue of Manson in discussing “Helter Skelter”.

Performing on the rooftop while recording the Let it Be movie/album.

Along with songs that aren’t as well remembered, you also get aspects of the band that aren’t as well remembered. The image of Lennon that’s pushed today is the peace lover, the one who sang “Imagine” and “Instant Karma” (two songs I like a lot, btw), but we forget the impish humor Lennon had, as well as the wordplay (as discussed in the chapters on “I Am the Walrus” and “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds”), and the incisive social observer of “A Day in the Life”, as Davidoff points out in his chapter. With the sentimentality of his solo works (which isn’t always earned), it’s easy to forget not only McCartney’s brilliance as a songwriter with the band, but also the technical sharpness he brought to the studio work (as Blauner admits, McCartney only contributed about 20 percent to “And Your Bird Can Sing”, but the song wouldn’t work nearly as well without it). When Harrison is mentioned in the context of the band, it’s often about the Eastern influences he brought to the table, but he could be as simple, direct, and powerful as McCartney and Lennon, as Prose discusses in her essay on “Here Comes the Sun”. Finally, Starr may have been the one who was most overlooked in the band, but as mentioned above, he contributed a key lyric to “Eleanor Rigby”, he sang a few of their most enjoyable songs, such as “Yellow Submarine” and “Octopus’ Garden” (as Schappell discusses in her chapter), and it’s his voice leading the chorus in the middle of the medley that gives Abbey Road its climax (as well as the drums that dominate the first part of the final part of the medley); “Golden Slumbers/Carry That Weight/The End” (as Moody illustrates in his chapter).

Many books have been written about the Beatles, and doubtless many more will be written about them in the future (Beatles historian Mark Lewisohn recently released the first of what is to be a trilogy of books about the band). It’s important to remember, however, they should be treated as a band, not as an institution, and books like In Their Lives go a long way towards making sure that happens.

It’s been 15 years since the first episode of The Wire – a show I, and many others, consider to be the finest show American TV has ever produced to date (I admit ignorance of shows from other countries for the most part – premiered on HBO. To mark that occasion, I’m going to talk a bit not only why I think it’s so great, but also to clear up a few myths and misconceptions that have built up around the show (as well as about “prestige TV”, the category it gets tagged in), in the hopes people who are hesitant about tackling the show may change their minds and give it a chance. In no particular order (and by the way, these are not direct quotes; I’m paraphrasing):

(1) “From what I’ve heard, it’s way too complicated to follow, so I’m going to be lost right from the beginning.”

In order to address this part, I of course must admit The Wire *is* complicated. Each season follows a different storyline: Season 1 takes on the drug war in microcosm through the eyes not only of the cops fighting it, but also the dealers, Season 2 deals with the eroding working class by following a group of dockworkers and the consequence of their leader making a deal with the devil, Season 3 looks at infrastructure among the police, drug dealers, and City Hall (along with being a thinly-disguised take on the War on Terror), Season 4 follows four young teenagers in school and why some go into the drug trade, and Season 5 asks why the media has not reported on the issues the first four seasons tackled. Also, with exception of Season 2 (and, of course, Season 5), these storylines, as well as many (though not all) of the characters carry over to subsequent seasons. Not only that, but the episodes are not stand-alone, and you need to keep all of the storylines and the characters in mind while watching. Finally, David Simon, the former Baltimore Sun reporter who created the show (along with ex-cop and ex-teacher Ed Burns) made it a point to not over-explain everything, so the viewer would have to really pay attention (Simon cared more about getting it right than catering to the average viewer). This was demonstrated most clearly in the fourth episode of the series, “Old Cases”, where Detective Jimmy McNulty (Dominic West) and his partner “Bunk” Moreland (Wendell Pierce) visit an old crime scene and solve the crime, while their entire dialogue consists of variations on “fuck”. So, yes, it is a complicated show.

But you know what other type of television show is complicated? Soap operas, which have several plotlines going on at once, and require you to remember characters from years past. There are also genre shows as varied as Battlestar Galactica, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Game of Thrones, Lost, and 24, among others, that have complicated storylines and mythologies, with loads of characters, and who, at their best, respect the intelligence of their viewers like The Wire does. And that’s not even mentioning the D.C. and Marvel shows that deal with arc-long seasons and many characters and storylines (themselves based on comic books with even more complicated mythologies and stories, as well as character arcs). If you’re able to follow any of those shows, I don’t think The Wire will be too much of a stretch for you.

(2) “Aside from being too complex and hard to follow, from what I’ve heard about The Wire, it sounds like homework. I just want something I can enjoy, you know?”

During the five seasons it was on the air, The Wire received a large amount of praise from TV critics, cultural commentators, and politicians (including former President Obama). The show has been praised for its intelligent storytelling, as mentioned above. It’s been called both a Greek tragedy on TV and also a novel on TV (drawing comparisons to Dickens and Tolstoy, among others). It’s been praised for being an indictment of how our cities are being left behind, as well as an indictment of the idea if you work hard, you can make a comfortable living for yourself and your family. It’s been praised for the realism of its storytelling and its characters, whether they be cops, drug dealers, junkies, dock workers, politicians, educators, students, or reporters. Finally, it’s been praised for it’s large, predominantly African-American cast, which had not been seen at the time (I’ll talk more about that below).

All of that praise is well-deserved, and may definitely make the show sound like homework. However, with some exceptions, most people who praise The Wire forget to point out it’s also consistently entertaining and funny. It may seem strange, not to mention insulting, to say a show with this much depth, intelligence, and tragedy (and there’s a lot of tragedy, especially in the next-to-last episode of every season) is also entertaining and funny (certainly, Simon seems to get irritated when people bring that up), but there is plenty of humor among the heartbreak. That scene I mentioned above with McNulty and Bunk is one example. Other examples include Omar Little (Michael K. Williams), the gay outlaw who robbed drug dealers, never pointed a gun at anyone not involved in the drug trade, and who became the breakout character on the show – testifying in court, Stringer Bell (Idris Elba), one of the major drug kingpins in the city, attempting to run a meeting of drug dealers using Robert’s Rules of Order, one drug dealer thinking he’s about to be killed, only to find out his colleague wants him to take care of his fish while he’s in hiding (“These are my tetras. We got Kimmy, Alex, Aubrey, and Jezebel here somewhere. I don’t know; she think she cute”), and many others. And while the show doesn’t go for the type of set pieces seen in other prestige dramas like The Sopranos (or, from what I’ve heard, Breaking Bad), or in genre shows like Buffy (with some exceptions, like a shootout between Omar and his crew with Avon Barksdale’s (Wood Harris) crew), there’s still entertainment value from the humor, the storylines, and the richly developed characters. Keep all of that in mind the next time someone makes it seem as if the show is just homework.

(3) “This show is yet another example of SWPL (Stuff White People Like); black misery being paraded on screen so that white people can get off on it.”

As African-Americans struggle to get represented in movies and on TV (it’s getting better on TV, though there’s still a long way to go), there’s been a debate not only about how much they get represented, but *how* they get represented. In certain quarters, African-American writers and commentators (along with those sympathetic to their view) gripe the only type of entertainment with African-American leads tends to be either historical pieces, or pieces where African-Americans are victimized in some way (or both). They want to see African-Americans in the same type of stories white Americans are in all the time – superhero movies, sci-fi, thrillers, romantic comedies, and so on. They also feel these historical pieces are done to soothe whites today with the idea racism is just a thing of the past, while the victim stories allow whites to feel superior as well by getting off on African-American misery.

All of these are valid complaints, and should be addressed (the fact Hollywood and indie studios have been so slow in addressing these issues is yet another example of their many failings). However, I think it’s highly unfair to tag The Wire with this complaint. True, there are plenty of characters here who are victims in some way: in the street, at school, in politics, in the police department, and in other areas. And while there’s almost no obvious racism on display (the closest is when a random constituent accosts Thomas Carcetti (Aidan Gillen) while he’s campaigning for mayor, and who complains about minorities with a term so archaic Norman (Reg. E. Cathey), Carcetti’s campaign manager, is more bemused than offended), there is racism implied, or even shown (most tragically in a police-involved shooting midway through the series). But the African-Americans in the show aren’t just defined as victims; they have lives outside of that. The show also has African-Americans not only in the drug trade, but in all other walks of life – blue-collar, white-collar, police, politician, civil servant, and more – and while they’re all competing for time with everyone else, you get a sense of their inner lives. None of them come off just as stick figures in a victim narrative. It helps Simon and Burns based them off people they came across in their previous careers, so, for example, Reginald “Bubbles” Cousins (Andre Royo), a drug addict and sometimes police informant, is depicted in a way more honest than we usually see with drug addicts, along with dignity and humor.

(4) “This show is yet another example of prestige TV’s, and popular culture in general, obsession with middle-aged white men, as well as Hollywood’s obsession with white savior stories.”

With the rise of quality TV (as well as quality in TV) in the last 20 years or so, it hasn’t gone unnoticed many of the acclaimed and talked about shows of that time (Breaking Bad, The Shield, The Sopranos) have centered on middle-aged white male main characters. In fact, much of the pushback that’s come against these shows recently has been because of that (along with another reason I’ll get to below). Although I would argue in many cases, the show is not celebrating its main character so much as skewering him (and would also argue, in the case of Mad Men – another prestige TV show that gets lumped in with that group – the show is as much about the women characters as it is about the middle-aged white male main character Don Draper), I certainly agree, as I said before, there should be more diverse viewpoints and main characters on TV (and in other forms of pop culture). But there was a recent article that lumped The Wire in with “middle-aged white male main character” shows, and that has me crying foul.

It’s true Jimmy McNulty is the first major character on the show we see, as he’s chatting up a witness at a crime scene (inspired by an incident Simon depicted in his great book Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets). And it’s true he’s the driving force behind the major plotline of Seasons 1 and 5, as well as figuring significantly into Seasons 2 and 3 (he was only seen in a few episodes of Season 4 because Dominic West was involved in a movie shoot, and also wanted to spend more time with his family). But as I alluded to above, there’s a large African-American cast on the show, and many of them get equal, if not more, screen time on the show. And while McNulty is praised on the show (both generously and grudgingly) as a good, dogged detective, the show also regularly called out for his womanizing (when the Major Crimes Unit is debating who to send undercover at a brothel for a sting operation, and McNulty walks in, Kima Greggs (Sonja Sohn), one of his colleagues, cracks, “Takes a whore to catch a whore”), his drinking (in one memorable scene, while driving drunk, he smashes his car, gets out, looks at it, gets back in, and smashes the other part), and the fact he feels because of his hard work and intelligence, he feels he can break the rules whenever he wants, whether fudging evidence or going against the bosses (as Bunk tells him at one point, “You’re no good for people, Jimmy”). And while McNulty’s work may eventually get results, most often, it’s not the results he wants; he never gets the main target he wants in the first three seasons, and what he does to try and catch the main bad guy in Season 5 proves to be the final straw for the police department (I’m being deliberately vague here for those who haven’t seen the show).

And that goes for the other major white characters on the show as well – or, at least, the ones who are trying to do good (unlike humps like Herc (Domenick Lombardozzi), a detective who remains almost as useless in Season 5 as he was in Season 1). Frank Sobotka (Chris Bauer), for example, is the main character in Season 2, a dockworker and union rep who is trying to save the port for the union and make things better for his colleagues. In order to do that, however, he’s made a deal with the devil in the form of a mobster known only as The Greek (Bill Raymond), which comes back to bite him during the season. To avoid this coming out, he’s regularly butting heads with Nat Coxson (Luray Cooper), an African-American union leader who feels Frank is overreaching in trying to protect the union (he thinks they should focus on protecting the pier instead of trying to dredge the canal, as Frank wants). Again, as it turns out, Frank comes up short. In Season 3, Carcetti, then a city councilman, starts his mission to run for mayor of the city because he thinks he can help the city, and while he does have genuine concern for trying to tackle the problems facing the city, in the end, his ambition overcomes his desire to do good. Finally, in season 4, Roland “Prez” Pryzbylewski (Jim True-Frost). a former detective, ends up a teacher in the Baltimore school system, but while he also wants to try and help the kids in his class – particularly Duquan “Dukie” Weems (Jermaine Crawford) and Randy Wagstaff (Maestro Harrell), two of the four kids who are the main characters that season (and whose fates are the most tragic) – and unlike Carcetti, doesn’t let ambition trip him up, the only person he ends up helping is himself; helping himself to learn to survive (it’s actually Howard “Bunny” Colvin (Robert Wisdom), another former member of the police department now involved in education, who ends up helping one of the four kids the most; Namond Brice (Julito McCullum), son of Barksdale enforcer Wee-Bey Brice (Hassan Johnson), who starts out in the drug trade but decides it’s no longer for him). This is hardly the stuff of “white savior” narratives, and Simon and Burns are consciously going out of their way to subvert those narratives.

(5) “This is yet another show that claims it wants to help combat the problems we face, but is merely trading in on cheap cynicism about our cities, our institutions, and our country.”

As we’ve seen all too often in this country the past few decades, there is a sizable minority in this country who believes racism is a thing of the past – assuming they admit it ever existed in this country in the first place – and it’s actually the people who are complaining about racism who are perpetuating the problem, and betraying a cynicism about this county. And according to this point of view, people who raise a stink about the way the poor are treated in this country are doing the same thing.

Obviously, I don’t think much of that point of view. Having said that, I will readily admit The Wire is very pessimistic about institutions, or at least at how these institutions have become today, due to a combination of factors (lack of money, bureaucracy, racism – both obvious and covert – government indifference, and more). However, if the show were as cynical as its detractors say it is – both the people in positions of power at those institutions (and their dislike of the show and what it brings up is understandable, if distressing) and the few cultural commentators who have taken issue with the show because of this (most notably film critic Armond White) – it wouldn’t be honoring the people who struggle to better their own lives, as well as those who try to make a difference and help others. There’s Bubbles, as I mentioned above, but also Dennis “Cutty” Wise (Chad L. Coleman), a former member of the Barksdale organization who tries to go back to the life when he gets released from jail, only to decide it isn’t for him, and opens up a boxing gym to try and get poor city kids to box. There’s Bunny, as I mentioned before, who, in Season 3, while he’s a major in the police department, comes up with an audacious plan to try and fight the drug war, and while it has its flaws, it also helps cut back on crime more than the war on drugs ever did. Finally, there’s Cedric Daniels (Lance Reddick), who heads up what becomes the Major Crimes unit in the first three seasons, and Lester Freamon (Clarke Peters), a detective in that unit. Both of them are taken for granted by McNulty at first – Daniels for being a company man, and for possibly having a dirty past (which we get hints at, but never really find out about), and Freamon for being an eccentric (he makes toy furniture) who was originally in the pawnshop unit for 13 years (“and four months”), but both of them not only turn out to be more than meets the eye, but both of them set out trying to improve the police department way of dealing with the drug war (as well as other police work), despite the bureaucracy they’re up against. That’s not cheap cynicism.

(6) “I’m tired of prestige TV because it’s working to hard to try and be ‘art’, and being more concerned with ‘arcs’ and ‘mythologies’, than in trying to tell a story.”

In his book Adventures in the Screen Trade, William Goldman wrote his famous phrase, “Nobody knows anything”, about how film executives have no idea what will work at the box office. However, he added, they do know what *has* worked in the past, and they figured if it worked in the past, it’ll work again, so they try to create past magic. That also goes for TV executives as well, which is why every new fall season, you see a lot of shows that borrow a lot from, or are blatant copies of, shows that were hits the previous season(s). When that happens, critics and commentators will pick through those shows (most of which are inferior at best, awful at worst), and while the good ones will point out how these lesser shows are learning the wrong lessons from the shows that became hits, other critics (even, unfortunately, the good ones), will start to turn on the type of show that impressed them in the first place. Such is the case with prestige TV nowadays; in addition to the criticism of the “white middle-aged male character” aspect (which, as I said before, is justified, though not in the case of The Wire), there’s also a wish TV shows could just go back to simple storytelling, with stand-alone episodes that were good stories instead of arcs and mythologies, and acting as if they were “better” than just TV.