The Criterion Blues Blogathon: The Criterion films of Nicolas Roeg

This is my contribution to The Criterion Blues Blogathon. Enjoy!

When Henri-Georges Clouzot once asked Jean-Luc Godard whether every film should have a beginning, middle and end, Godard famously replied, “Yes, but not necessarily in that order.” Godard aside, most movies today do have a beginning, middle and end in that order. It’s a method of storytelling, to be sure, that’s produced some of the greatest films ever made. But there’s nothing wrong with filmmakers trying to break up that method of storytelling, so that things aren’t in order. One of the few directors who challenged this way of storytelling on film was Nicolas Roeg. Roeg was known for his fragmented narrative, of having flashbacks and flash-forwards (terms he’s claimed he’s never really understood), and challenging viewers in more ways than just in the narrative. When Roeg was still making films (his last theatrically released film, Puffball (2007), only had a limited released in the U.S.), his style received a mixed reception from critics and audiences, but nowadays, Roeg has been receiving plaudits from filmmakers (Danny Boyle and Steven Soderbergh both praise him on a recent DVD), and from Criterion, which has released five of his films on DVD. It’s those five films that I’d like to focus on.

———————————————————–

Roeg, of course, started out his career working in the camera department, first as an assistant cameraman in 1951 (for the film Calling Bulldog Drummond), then moving up to camera operator (on such films as The Man Inside and The Sundowners), and eventually cinematographer on such films as Lawrence of Arabia (for which he shot the second-unit cinematography), Masque of the Red Death, Fahrenheit 451, the 1967 adaptation of Far from the Madding Crowd, and Petulia. In 1970 came his first film as director, Performance, where he shared a directing credit with Donald Cammell. Though this tale of a gangster (James Fox) on the lam who hides out with a reclusive rock star (Mick Jagger) features Roeg on cinematography, and also has a fractured narrative (not to mention casting a musician in one of the lead roles, which he would do twice more in the next decade), it’s considered as much a film by Cammell as it is by Roeg. Walkabout (1971), released a year later), would be Roeg’s solo directorial debut.

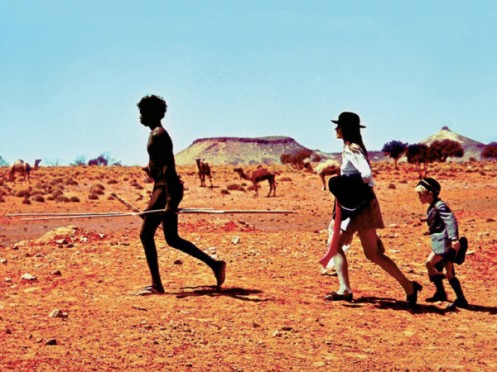

The girl (Jenny Agutter) and the aborigine (David Gulpilil) try to help the boy (Luc Roeg).

I’ve always put Roeg in the category of filmmakers who are interesting even though they’ve never quite been able to get the film that’s in their heads onto the screen, which is ironic since Roeg has insisted he never plans anything out in advance when it comes to shooting. Walkabout, for me, is the film that’s Roeg’s most successful attempt at putting it all together. Based on a children’s novel called The Children by Donald G. Payne (writing under the name James Vance Marshall), it tells the story of two children, a teenage girl (Jenny Agutter) and her younger brother (Roeg’s son Luc, billed here as Lucien John), who are stranded in the outback area of Australia, and the help they receive from an aborigine boy (David Gulpilil) who’s about the same age as the girl (as the opening credits explain, when an aborigine boy reaches the age of 16, he goes out into the wild to live off of the land, which is called going on a “walkabout”). The aborigine helps the two children find water (which is their major need in the desert) and food, but while the boy develops an instant liking to the aborigine (the feeling is mutual), things are more complicated with his sister.

Roeg and playwright Edward Bond (best known at the time for the play Saved), who wrote the screenplay, made some crucial changes to the novel. First, while in the novel, the boy and girl’s parents died in a plane crash that stranded the children, here, the boy and girl get taken to the outback by the father, who tries to shoot them before killing himself (the boy doesn’t know what’s going on, but the girl does, and manages to flee with her brother before their father commits suicide). Also, the way the aborigine meets his eventual fate in the movie is different than in the novel. Finally, they play up the girl’s budding sexuality (including a scene where the girl swims nude in a lake, though it should be said it’s done without any voyeurism), which also contributes to the aborigine’s fate. But mostly, Roeg and Bond are faithful to the essential story, and the author’s way of capturing the landscape. Obviously, a lot of that can be done through the photography, and Roeg, who also served as the film’s cinematographer (the last time he’d do so on a feature film), brings out the beautiful parts of the landscape while also making clear how it can seem forbidding and dangerous, and all of this without turning the film into a travelogue. Roeg also follows another Godard dictum here in showing the interior lives of his characters by staying outside, and using the landscape to do so. That becomes especially apparent near the end, when the aborigine does a dance for the girl that he clearly means one way and the girl takes another way.

The three on their journey.

While Agutter had been making movies for nearly a decade before this film, Walkabout was Luc Roeg’s first (and, as it turns out, only) film as an actor, and the same with Gulpilil, but Roeg gets natural performances out of all three of them. Luc Roeg comes off as a natural child, being able to relate to some things immediately without truly understanding everything that’s going on. Gulpilil, one of the few well known aborigine actors in Australia (he has also appeared in such films as Mad Dog Morgan, Crocodile Dundee, and Rabbit Proof Fence, is primarily a dancer (a documentary on the Criterion DVD about his life and career shows him how to teach people aborigine dance), and his fluidity of movement certainly suggests that. And he and Roeg work hard to try and avoid the “noble savage” cliche (not entirely successfully, it should be said; it’s the one failure of the film) and make him into a distinctive character. Finally, while Agutter is the one experienced actor among the three, she works well with the others, become like a mother figure to Roeg’s character while still being enough of a teenage girl to be convincingly freaked out by what she’s going through. In Australia, the novel has long been considered a children’s classic, and Roeg’s film remains a classic in its own right.

————————————————————

As I mentioned before, Roeg started out as a cameraman, and has therefore always considered movies visual stories, and screenplays, and the written word in general, to be blueprints and not movies. What makes that ironic is Roeg has not only worked with playwrights (who hold the written word paramount), bus has often adapted the written word of novels, plays, and short stories to the screen. Such was also the case with Roeg’s next film, Don’t Look Now (1973), which was adapted from the short story by Daphne du Maurier.

Laura (Julie Christie) trying, and failing, to convince John (Donald Sutherland).

As with the story, the movie follows John Baxter (Donald Sutherland), an art restorer, and his wife Laura (Julie Christie) during their time in Venice. Part of the trip is for business – John is restoring a church – but they’re also there because John hopes it will help them both, especially Laura, get over the death of their daughter Christine (Sharon Williams). Early in their trip, at a restaurant, they see two old women who are sisters – Wendy (Clelia Matania) and Heather (Hilary Mason) – who seem a bit bizarre but harmless, and who are staring at them. Wendy gets something caught in her eye, and since Heather is blind, Laura volunteers to help her in the ladies’ room. Heather also claims to be psychic, and in the bathroom, she claims she has a message from Christine, telling Laura and John not to worry, which causes Laura to faint later, but also makes her the happiest she’s been since Christine died. John doesn’t believe this, and doesn’t want to believe, but it turns out John may be psychic as well in his own way, which leads to danger for him.

Again, Roeg, along with writers Chris Bryant and Allan Scott (the latter of whom went on to write or co-write four feature films and one made-for-TV film for Roeg), changes du Maurier’s story while still keeping the essence of it. In the story, for example, Christine died of meningitis, while in the movie, she drowns in a pond outside their home, and while wearing a red mac (the color red appears as a motif throughout the entire film, an invention of Roeg’s), and is tied in to show John’s premonition (he runs outside without hearing a scream, though he’s too late). Also, the movie adds the famous sex scene between John and Laura, which is intercut between the two of them getting ready (in interviews, Roeg said he wanted to show one moment of intimacy as a contrast to the many disagreements they have throughout the film, but it’s also implied they’re trying to have another baby to try and replace Christine). Still, Roeg keeps the essence of the story all the way until the end, when John makes two tragic mistakes.

Christine (Sharon Williams) in the woods before her death.

Roeg, cinematographer Anthony B. Richmond (who went on to shoot two more features and two made-for-TV movies for Roeg), and editor Graeme Clifford (who went on to become a director in the 80’s) try to avoid using the obvious locations in Venice, using the walkways, the age of the buildings, and the bleached out colors to help create menace. And while there are flashbacks (often to the time of Christine’s death), they aren’t used in a flashy way, and John’s other “premonitions” aren’t juiced up, so Roeg can’t be accused of hyping the material. Yet, even given how the tale winds up, and the inclusion of a subplot involving a serial killer, I must admit I find myself sympathizing with Pauline Kael, who felt Roeg’s technique was so cold it never allowed us to feel anything for the characters, and that it was dressing up Gothic material that didn’t need dressing up. Despite the efforts of Sutherland and Christie, who are both very good, the film always keeps us at a distance from the characters, especially the supporting ones (Roeg’s attempts to show ambiguity regarding the sisters – as to whether they’re frauds or not – also comes as cheap). Of all the films of Roeg’s that have been released on Criterion, Don’t Look Now is my least favorite, even with all that’s good in it.

————————————————————-

One of the more important aspects of Roeg’s career that needs to be examined is the way he uses music, particularly recorded music, to underscore the action. The radio the young boy carries around in Walkabout (playing Rod Stewart’s “Gasoline Alley” and Warren Marley’s “Los Angeles”, among other songs), Mick Jagger’s electrifying performance of “Memo From Turner” in the hallucinatory sequence in Performance, and his staging of Verdi’s “Un Ballo in Maschera” in Aria being among the highlights. Along with that goes his willingness to use musicians in leading roles in films. Probably no better example of that tendency came in Roeg’s following film, The Man who Fell to Earth, with David Bowie in the title role.

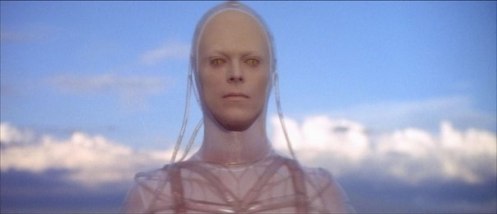

Thomas Jane Newton (David Bowie).

Bowie plays Thomas Jerome Newton, a man who comes to New Mexico and starts a technology company thanks to Oliver Farnsworth (Buck Henry), a patent lawyer who helps patent his inventions, and Dr. Nathan Bryce (Rip Torn), a cynical, womanizing chemistry professor whom Newton hires as his science consultant. Newton also finds himself falling in love with Mary Lou (Candy Clark), a hotel maid who later helps him in his business. Gradually, we find out what that business is really for; Newton is actually an alien from another planet who’s trying to raise enough money so he can build a spaceship, go back, and rescue the survivors, including his wife and children, who are suffering because the planet has run out of water. However, the U.S. government, in the form of Peters (Bernie Casey), has other ideas.

I’ve never read the Walter Tevis novel the movie is based on (adapted by Paul Mayersberg, a former film critic who also went on to write Croupier over two decades later), so I don’t know how Roeg handled the transition from novel to screen. I know Roeg’s use of flashbacks to Newton’s planet, where he and his wife (also played by Clark) and children are struggling to survive, give us the emotional connection that I was missing in Roeg’s previous film. And Roeg doesn’t try to accentuate Bowie’s already alien persona any more than necessary (we don’t see him in his alien guise while on Earth except for two scenes, and only for a short time in both of them). He grounds how alienated Newton is from everyone else in the normal, everyday circumstances of Newton being addicted to watching television, and later, drinking alcohol (an unintended resonance to the addiction storyline is Bowie himself was going through a drug addiction at the time). as well as seeing how everyone one else eventually ages while Newton, essentially stays the same, at least until maybe the end. And once again, Roeg, working here again with Richmond and Clifford, uses the landscape to play against Newton without going overboard with it.

The alien (Bowie).

The American release was cut by 20 minutes, and some scenes were rearranged differently. The Criterion version restores Roeg’s original intent, and makes things clearer (along with, as is Roeg’s method, being more sexually explicit). It’s still somewhat confusing at times – it’s never really made clear to us why Bryce ends up selling Newton out – but it’s always dazzling to look at, thanks to the flashbacks (also shot in New Mexico), and its portrayal of an alien not as a menace, nor as a “pure” being, but someone subject to the same desires as all of us. Bowie has been a man of many personas over the course of his career, and this is one he wears rather well, while Henry is perfect as the ultimate corporate drone, and Torn does well in playing against type as someone more intellectual than emotional. Clark can strain at times, but she has good chemistry with Bowie, and brings off a tough scene when she finds out who Newton really is. Bowie was originally supposed to write the music for the movie as well, but for whatever reason, that didn’t work out; still, the music for the film is well used, as well as the collage of images from the televisions Newton is glued to. The Man who Fell to Earth is the type of film I was thinking of when I originally claimed Roeg could never quite get the movie in his head onto the screen, but it’s definitely an engaging and interesting movie all the same.

————————————————————-

Much has been made of the relationship between directors and actors who have served as their on-screen muse. John Ford and John Wayne, Akira Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune, Martin Scorsese and Robert De Niro; these are all familiar pairings to us. But there are also the intertwined careers of directors and actresses, such as Josef Von Sternberg and Marlene Dietrich, Ingmar Bergman and his many leading women (particularly, of course, Liv Ullmann), and Woody Allen with Diane Keaton and then Mia Farrow (more recently, Nicole Holofcener and Catherine Keener as well). Then there’s Roeg and Theresa Russell, an actress who, at the time they got together, was known only for playing a small part in Elia Kazan’s adaptation of The Last Tycoon, and as Dustin Hoffman’s girlfriend in Ulu Grosbard’s Straight Time. While the seven films the two of them made together (six features and one short that was part of the anthology film Aria) aren’t as well known as his 70’s films (and Cold Heaven, adapted from the novel by Brian Moore, is definitely a misfire, albeit a daring one), two of them are among Roeg’s very best. The first one they did together was Roeg’s most controversial, Bad Timing (1980), released in the U.S. with the subtitle A Sensual Obsession.

Milena (Theresa Russell) seduces Alex (Art Garfunkel).

Roeg’s previous films, even though they had a non-linear narrative, did have a relative order that viewers could follow, but Bad Timing (which Roeg made after an attempt to make a Flash Gordon movie fell through) contains Roeg’s most fractured narrative yet (written by Yale Udoff). Nominally, it’s about two American expatriates in Vienna – Alex Linden (Art Garfunkel), a psychiatrist and professor, and Milena Flaherty (Russell), a recent divorcee, who get involved in a passionate affair, and about how Netusil (Harvey Keitel), a police inspector, investigates what was apparently a suicide attempt by Milena. But the film is told in flashback after the opening credits scene of Alex and Milena in an art gallery (scored to Tom Waits’ “An Invitation to the Blues”), flashing back and forth between Milena in the hospital – as well as Netusil questioning Alex as to how she got there – and Alex and Milena’s relationship. This adds up to Roeg’s most fragmented narrative yet.

In an interview on the Criterion DVD, Roeg and producer Jeremy Thomas talk about how the film is essentially a memory piece, and how the editing style (the film was edited by Tony Lawson, who went on to edit eight more films of Roeg’s) helps bring that out. A lot of that is through the juxtaposition of images, in which we can go, for example, from Alex and Milena having passionate sex to Milena on the operating table, and from Netusil entering Alex’s room in the present to a flashback of Alex and Milena in that room. It also involves cutting from the physical objects in the room. Roeg may only really handle one or two (at most three) people in a room, or an area, at a time, but he’s alive to the culture people engage in (when he glances at a collection of Harold Pinter plays that Milena is reading, Alex can guess she’s having an affair with an actor), and the way a person’s belongings can help define them (Milena’s room, which is full of belongings and clutter, seems alive in a way Alex’s more orderly room doesn’t, which helps reflect their personalities). The film is also a study of two people seeking control. Alex is trying to control and define Milena, who doesn’t want either (which is both the cause of the excitement and tension in their relationship), while Netusil is trying to impose control over Alex by getting him to admit to what he believes really happened to Milena that night.

Netusil (Harvey Keitel) questions Alex.

There was a lot of controversy surrounding the movie when it came out, in reference to the explicitness of the sex scenes and other imagery, to what really happened to Milena (which caused a member of the British film company the Rank Organization to call it “a sick film for sick people”), and even surrounding the casting of Garfunkel and Keitel. But as disturbing as what happens to Milena is, it does speak to Alex’s need for control (in a sick, perverted way, of course), and Roeg and Richmond (Tony Lawson, who had edited Barry Lyndon for Stanley Kubrick, was the editor here; he went on to edit eight more films for Roeg) are careful not to be exploitative in rendering the scene. As for Garfunkel and Keitel, I feel they actually work for the movie. There’s always been something closed off about Garfunkel, and that works here for his character, but Roeg also gets him to be angrier than he’s ever been on screen, while Keitel, his faltering with the Viennese accent aside, is surprisingly restrained as the methodical (if not quite as intellectual as he thinks) inspector. Rounding out the male roles is Denholm Elliot as Milena’s ex, and the one man who never sought to control her, and Elliot brings a welcome melancholy to the role, as well as pent-up anger. The film, however, belongs to Russell. This is definitely a playing-to-the-seats performance, but it works for the character, as Milena is always struggling against Alex’s conception of her, and is forever reacting to that. And she remains one of the sexiest presences I’ve ever seen on screen (it’s no accident Pete Townshend originally wrote the Who song “Athena” as an ode to Russell, called “Theresa”). Bad Timing continues to provoke to this day, but I think it stands as one of Roeg’s best.

————————————————————-

Bad Timing wasn’t well received by critics or the box office, and Roeg’s follow-up film, Eureka, starring Gene Hackman as a prospector, ended up being barely released, to critical and public indifference. However, Roeg managed to recover to adapt, of all things, a play, when he took on a film version of Terry Johnson’s play Insignificance, and delivered yet another one of his best films.

The Actress (Theresa Russell) demonstrates the theory of relativity to The Scientist (Michael Emil).

As with the play, the film takes off from the famous image of Marilyn Monroe’s white dress blowing up while she’s standing over the subway grate in Billy Wilder’s The Seven Year Itch. Taking place over the course of one night, it imagines that Monroe (Russell), known only here as The Actress, goes to a Manhattan hotel where, as it happens, Albert Einstein (Michael Emil, brother of filmmaker Henry Jaglom), known here only as The Scientist, is staying. Einstein is in town to speak at a peace conference, though Joe McCarthy (Tony Curtis), known here only as The Senator, has other ideas; he wants Einstein to testify in front of HUAC and denounce communism. Meanwhile, Monroe’s ex-husband, Joe DiMaggio (Gary Busey), known here only as The Ballplayer, just wants Monroe to come back to him, but acts crazy jealous around anyone who shows interest in her (we first see him watching and seething during the recreation of that famous shot from Wilder’s film). Monroe, on the other hand, just wants to discuss with Einstein the theory of relativity, the creation and meaning of the universe, and other matters of, well, insignificance.

The main subject of Johnson’s story seems to be celebrity, in particular how a public persona can often hide what’s really underneath. Roeg’s contribution to this was, as usual, to show people’s pasts through flashbacks, from Monroe in auditions being ogled by talent agents to Einstein in war-torn Europe, to DiMaggio as a young player and McCarthy as an altar boy. And what the characters talk about, particularly when Monroe is demonstrating the theory of relativity to Einstein, is the clearest way of illustrating the huge gap between what we think we know and what we actually know, whether about the theory of relativity (Monroe admits while she can explain it, she doesn’t really understand it) or about a person in general (McCarthy thinks he can get Einstein to testify simply by either appealing to his intellect or by bullying him, while DiMaggio thinks if he cajoles Monroe enough, he’ll get her to come back to him. Both of them are wrong). And despite the fact most of this (except for the scene recreation and the flashbacks) is set in the hotel room and hallways, Roeg, Lawson, and cinematographer Peter Hannan (who shot, among other films, Monty Python’s Meaning of Life and Withnail & I) never make it seem stagy.

The Senator (Tony Curtis) confronts Einstein.

Because the characters are not really DiMaggio, Einstein, McCarthy and Monroe, the actors are a little more free to play around with the material. Busey, for example, may seem at first to be too energetic and mercurial to play the notoriously aloof DiMaggio, but he carries himself like an ex-athlete, and makes that manic nature work for him as someone who doesn’t like the fact the world no longer acts the way it should now he’s retired. I’m not familiar with Emil’s other work as an actor (I’m not a fan of Jaglom’s films, in which Emil was a regular), but he captures both Einstein’s intellect and his sadness that the world was becoming something more horrible than he imagined. Curtis gives one of his best performances as McCarthy, re-imagining him as if Sidney Falco hadn’t been killed, but had gone on to outdo J.J. Hunsecker in fake charm, intimidation and manipulation, though showing the sweat much more. Finally, while Russell may be nobody’s idea of Monroe, and comes off as a little too affected at first, gradually I warmed up to that once I realized her conception of Monroe was of someone aware of the affectation but resigned to it nonetheless even as she struggled to break free of it. For the movie, Roeg and Johnson added an elevator operator played by Will Sampson who claims Einstein is part Cherokee – meaning he has a deeper understanding of the world than anyone else – and that comes off as borderline patronizing (though Sampson at least plays the part well). And some of the scenes drag at times. Still, overall, Insignificance serves as an entertaining meditation on our knowledge of the world, or lack thereof.

————————————————————-

After that film, Roeg’s one major film was his adaptation of Roald Dahl’s classic children’s novel The Witches, with the help of producer Jim Henson’s creature effects and Anjelica Huston’s terrifying performance as the villain of the film. After that, however, his career dried up; aside from an ambitious but flawed “straight” made-for-TV version of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, with Tim Roth as Marlow and John Malkovich as Kurtz, Roeg was reduced to directing episodes of TV and soft-core cable porn such as Full Body Massage. In the past decade, Roeg’s career has been rightly re-evaluated, and he’s considered one of the best filmmakers to come out of Britain in the 70’s, and Criterion showcasing these five films of his stands as fitting tribute.

Superb article and you really pinned down Roeg’s career here. I haven’t seen everything. One notable omission is Walkabout, which I have been meaning to get around to, but I’ve seen the other major works you discussed here up to Insignificance. He can be a mixed bag, and I agree that sometimes the film in his head probably didn’t end up on screen. It is interesting that you dislike Don’t Look Now, as that seems pretty popular and is my favorite of his, but he is a polarizing filmmaker. You pretty much noted that with The Man Who Fell to Earth.

Really great post! Thanks for contributing to the Blogathon!

Thanks! It was a pleasure. And Walkabout is definitely essential viewing, so I hope you’re able to get around to him sooner or later.

I haven’t seen many Roeg films, and I’ve read even less about him. So your essay was a great introduction to this under-recognized director. It was sad to read the decline of his career in later years but, as you pointed out, it’s a good thing Criterion is honouring his work in this way.

Thanks for joining the blogathon and sharing all your research with this comprehensive portrait of Nicolas Roeg!

Thanks! Which of his have you seen?

Does Farenheit 451 count, when he was DP? Saw Walkabout (as you know, it has a beginning you never forget) and, don’t ask me how, but part of Sweet Bird of Youth with Elizabeth Taylor. Have not seen many at all… But you’ve encouraged me to seek out more of his work.